What Went Wrong with Amazon Go?

Dive into the Amazon Go Saga complete with ex-employee perspectives and a technologist's insider knowledge.

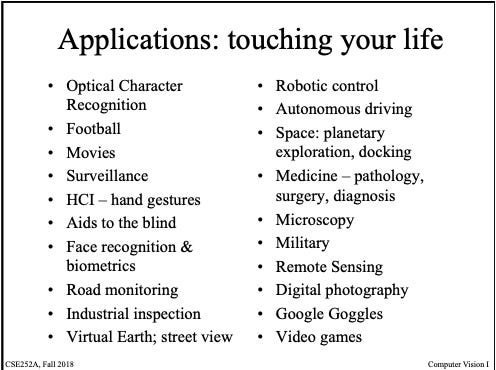

In the world of AI, computer vision has come a long way. From homography, the math that gave us PDF Scanners, to AI-based classifiers, the math-ish models that gave us Face ID, technologists have made many strides in helping a robot see the world the same as we do.

But in our haste to see the trees in all their pixelated glory, we may have been missing the forest.

In 2024, cameras may be observing us in a variety of ways and in unexpected places: our phones, our laptops, our public roads and institutions, our Airbnb stays. In the past decade, as cameras got ubiquitous, so too did the applications.

High tech companies have eagerly tried to show us how well their robots can pick and sort based on a visual feed, how cars can stay within their lanes, and how fires can be spotted before they grow wild.

But perhaps the most popular and widely hailed application of all was Amazon’s ‘Just Walk Out’ Technology. Amazon’s alluring premise was simple: Go inside an Amazon Fresh or Amazon-affiliated store, grab what you’d like and walk out. In the background, your Amazon account will get charged with the required amount. No more messy checkout lines or fumbling with wallets!

When the ‘Just Walk Out‘ tech debuted in 2018 people both in and outside the tech biosphere raved about the Go Stores. One reporter said that he spent 53 minutes at a Go Store and saw the future. Another NYT reporter mentioned how shoplifting will become a thing of the past. I have to admit that the Go application did hold a fascinating appeal. One that conflated tech’s ‘The Future is Here! And Now!‘ messaging.

Unfortunately, like a lot of things that pour out of Silicon Valley, this technology too was not what it seemed.

So what was really going on behind the cameras?

Every time you walked into a ‘Go‘ store, there might be a team of Indians watching your every move1. Almost every instance that you picked up or replaced a product would be tagged as an “interaction“, passed through an AI classifier, and when that failed, forwarded thousands of miles to humans on the other side of the globe.

The tales spun by Amazon for publicity differed wildly from what actually went on.

The Go classification model, like many classification models, suffered from a lack of accuracy. It was not always its fault, of course, simple things can change how an AI perceives the same item: lighting, the viewing angles, the myriad of rotational degrees that the object may find itself in, the camera’s own calibration specs, the scale of the image, and so on.

Knowing this, Amazon couldn’t very well show its investors and adoring fans a faulty visually floundering cashier, could it? And so, Amazon secretly developed a back-up.

For every shopper who craned their necks and watched the store’s cameras in awe, there was an Amazon worker peering tirelessly right back at them, watching their every choice2 and verifying the items that they do pick up. If the AI model made an error, they would swoop in to re-classify and assign the right tag.

The questions typically answered by the human associates ranged from what the shopper had picked up and when to who had picked it up and whether an item was in the process of being picked up or replaced. Sometimes answering these questions took time and in those instances the shopper would receive their bill later than expected. For a few unlucky shoppers, the bill has arrived several days late. Maybe there was an holiday in India?

.

I first heard of the Amazon Go taggers two years ago. A friend of mine who worked at Amazon Go’s India team told me about this - let’s call it what it is - scam. The name of their team was CXQO or ‘Customer Experience and Quality Operations‘. Their duties ranged from image labelling and curation of training datasets to answering the “inquiries“ received in real-time from the Go stores.

These Indian workers who were paid less than 3500 USD a year had to spend strenuous hours watching and verifying shopping behaviors in America. Some of them had to always be on call, and always ready to fix the AI’s mistakes. He said that the work was highly repetitive AND required incredible levels of concentration for long lengths of time. The inhumane working conditions finally made him drop out of the program.

When I heard his story I was fascinated and, frankly, disheartened. I had never before heard of the Indian elves that help keep up present-day Santa’s appearance. In hindsight, it makes perfect sense. Of course, Amazon didn’t develop a 100% accurate computer vision system that can work under so many variable conditions. Of course, they couldn’t have done it within a few years.

This news is finally being made public. Last year, The Information reported how 700 out of every 1000 sales, or 70% of the just-pick-ups, had to be re-classified by the Indian employees. In human-in-the-loop AI slang, this metric is referred to as “IPk“ or “Inquiries per thousand“.

Rumor has it that the actual re-tags may be greater than 100%. The IPk values, in decimal, were typically greater than 1, implying that every product interaction required at least one verification by a human.

On the other hand, Amazon claimed the number to be as low as 5%, and it maintains that the number is actually that low. It could be that the metric they publicize may have been confused with another amongst all the jargon. But mistaking a boulder for a stone doesn’t change the fact that the boulder exists, and so too can the stone.

Meanwhile, self-checkout stations at other major retailers are being scaled back and giving way to human cashiers (who are in need of the work!) once again. In this climate, Amazon is backing away from its costly mistakes as well.

Some of the reasons for its failure are obvious. Some not so:

Number one, maintaining a ‘Just Walk Out‘ store is expensive. Think of all the costs: the cameras, the NVIDIA GPUs, the sensor rigs and the intense energy usage, the highly paid AI engineers in the US and the not-so-well paid real detectors in India.

Number two, the technology can rapidly get outdated. In a country like America, where food and beverage CPGs3 can pop up like pimples, an automatic cashier is in need of constant updates. To perform well, these AI systems need lots and lots of data and at regular intervals. A momentous task that may have turned out to be infeasible.

Number three, and here’s the important one, the Go technology is riddled with biases. Much like other human recognition software, Go’s tech was also largely trained on able-bodied adults. And just like Clearview, the possibilities of misuse and exclusions are rife. For example, if you wanted to shoplift from a Go-like store, take along a small child with sticky fingers. Both the AI and the Humans-in-the-loop may be largely stumped4.

Number four, the Seattle-based Go organization had become a hotbed for office politicking. Though Amazon and Big Tech enjoy pushing forth an image of entrepreneurship and innovation, the sad truth is that they are now bloated bureaucracies complete with a hierarchy of managers filled with suspicion of the fresh ideas from its younger employees.

Amazon is now attempting to extricate itself from this visual nightmare by switching to Dash Carts. New Amazon Fresh stores will come outfitted with self-checkout stations that one can wheel around instead of meeting at the end. These Dash Carts are equipped with barcode scanners, a screen to display your purchases, a scale for weighing and a few cameras to look out for theft.

If that doesn’t sound impressive and reflective of the millions of dollars spent on making this product, you would be right.

But the Dash Carts were not always such simplistic machines, they too were once outfitted with high-tech cameras and deep learning models. However, the cost of the earliest prototypes is estimated to be ~35 times more expensive than the current avatar. People who used to work closely with the product joke that if the first version was a Mercedes Benz then the current one is a Honda Fit. Necessity, cost, and a lack of demand for over-the-top tech, has forced the Amazon execs to reconsider their product offering.

In the end, one has to wonder how much value there is in building a shopping cart that operates almost the same as existing self-checkout stations. If I was a grocery store owner, and Amazon tried to sell me its Dash Carts, I would be hard pressed to find a reason to say yes.

The worst part in this whole drama is how the workers are being treated. Layoffs at Amazon Go and its extended teams may be around the corner. Engineers in certain teams have been abruptly faced with Big Tech’s go-to ultimatum, i.e., to either find a new role within the organization soon or just walk out.

Perhaps not your every move.

Exaggerated for humor only!

Consumer Product Goods

Just kidding, of course!

I used to work with Amazon Go and all the reasons listed here are on-point. Good read!