The Economies of Renting

My story as a Serial Renter with no hope (or dream) of buying a home in this country.

By December 2023, I had lived in 6 different apartments in 6 years. By 2024, the number is going to inch up to a 7.

From 2017, the year I first started living in the US to now, I have roughly had to move once every year. In fact, moving has become so normalized that having a steady reliable home sounds like a pipe dream to me. And I’m not alone.

Millenials have historically lagged behind previous generations in achieving the home-buying dream. The economic reality is more complex for us than it was for older generations. The 2008 financial crisis was a setback for older millenials, and now, younger millenials are living through multiple crises: Covid, wars, inflation, high interest rates, a dearth of reliable employment, lack of housing supplies, etc., which makes home-buying harder than it should be.

For the most part, we have all collectively decided to put up with our lot and RENT. Sadly, not all rentals are equal. The first shocking thing I learnt about the US rental market is how segregated it can be. Your rent depends on where you live. So does the cost of your auto insurance. So does your access to good hospitals and good food and restaurants. The more you pay, the better the neighborhood, and the healthier your life will be.

Before covid, my work required me to live close to the city. And as a young ~25 year old, I also preferred living in the city. At the beginning, I lived in an OK, mostly immigrant neighborhood but the year after that I moved into a wealthier, whiter, neighborhood. I wanted the perks, even if it drained more of my paycheck, and I wanted the added safety. But I couldn’t stay in the wealthy neighborhood for long either. One year later, rent in Boston skyrocketed as Covid restrictions petered out. Average rent from 2020 to 2021 shot up 15.7%, whereas my pay raise was a paltry 2.5%.

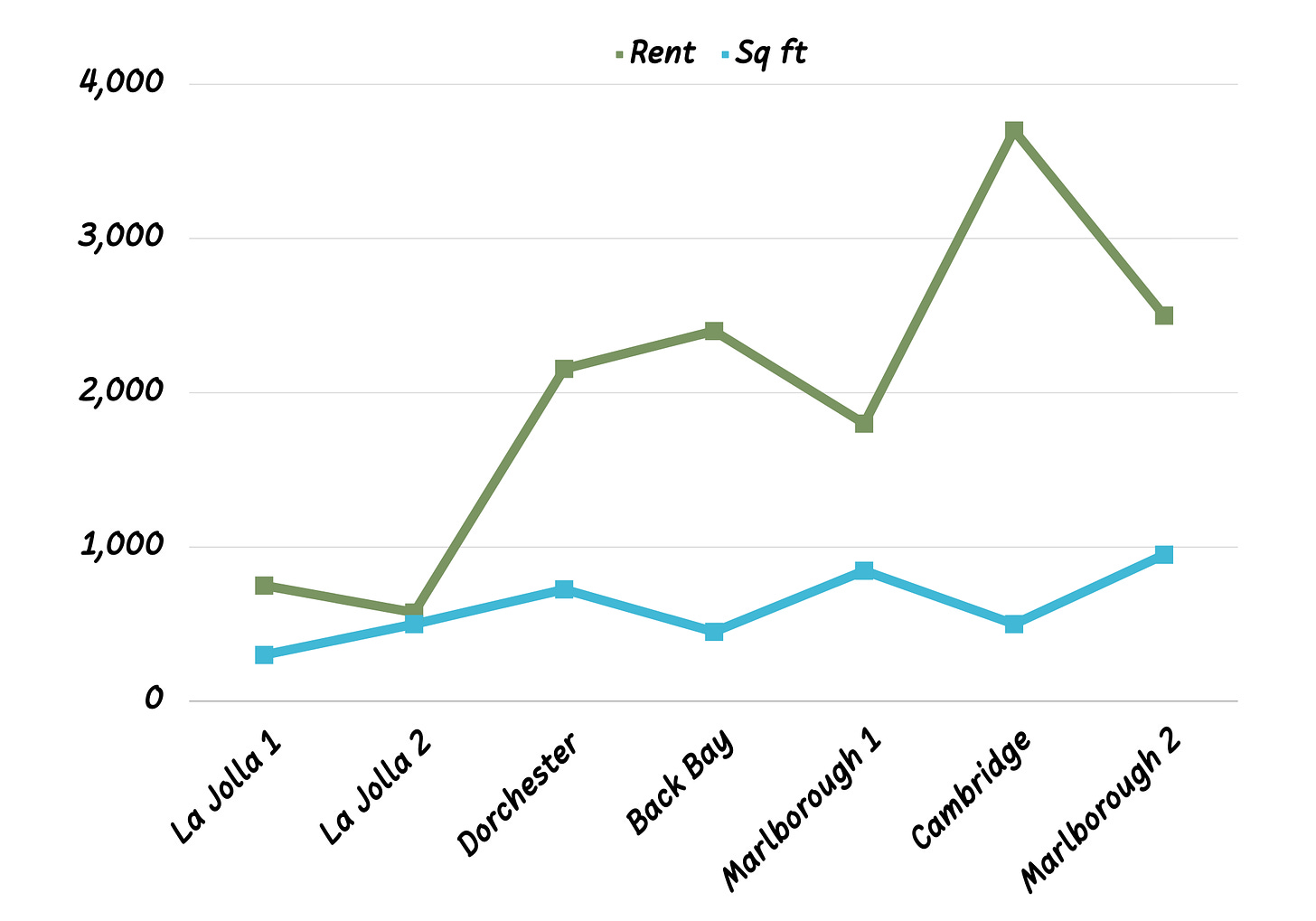

Which was when we packed up and moved to an apartment in the suburbs (Marlborough, MA). The rent to square ft. ratio decreased dramatically. We got more space, we got a dog, we found an amazing community, and we had to pay less. Yay for remote work. (The flip side, to be perfectly honest, is being away from good restaurants, theaters, and other places to hang out.)

I’ll try not to bore you with all my moves. In short, I did move back and forth between the suburb and the city a few times depending on how frequently I was forced to go into the office. With each move, I started noticing the different asks on our budget. I observed that the costs of renting can be broadly split into three categories: the primary costs like rent and utilities, the secondary costs like the cost of moving, purchasing stuff to suit the new rooms, amount you spend on parking, etc., and the tertiary intangible costs associated with a nomadic lifestyle such as the loss of local friends and community, the stress of moving and living with the constant scary unknown.

I. Primary Costs

Thinking more about the rent and utility costs, I had several questions.

Who decides the rent? Who owns most of the land / homes in Boston? Why do we have to put up with old crappy apartments that gobble up a much bigger bite out of our pay checks?

Besides the straightforward reasoning I mentioned earlier such as the neighborhood, supply-vs-demand, etc. I wanted to learn more about who was controlling these prices. Many of the Boston area apartment communities have a few (extremely wealthy) owners like the Corcoran Group and Avalon Bay. Around the Kendall Square area, I was surprised to find that many of the apartments are in fact owned by MIT. And the rent was exorbitant. (I speak from experience - last year, my landlord had been MIT.)

In essence, institutions and corporations are owning most of the limited land in Boston and were buying up even more of the real estate as investments. Nowadays, 1 in 5 buyers are investors who are ready to pay in cash and never actually live in those homes. How could any normal paycheck dependent family compete with that?

And the wealth gap widens.

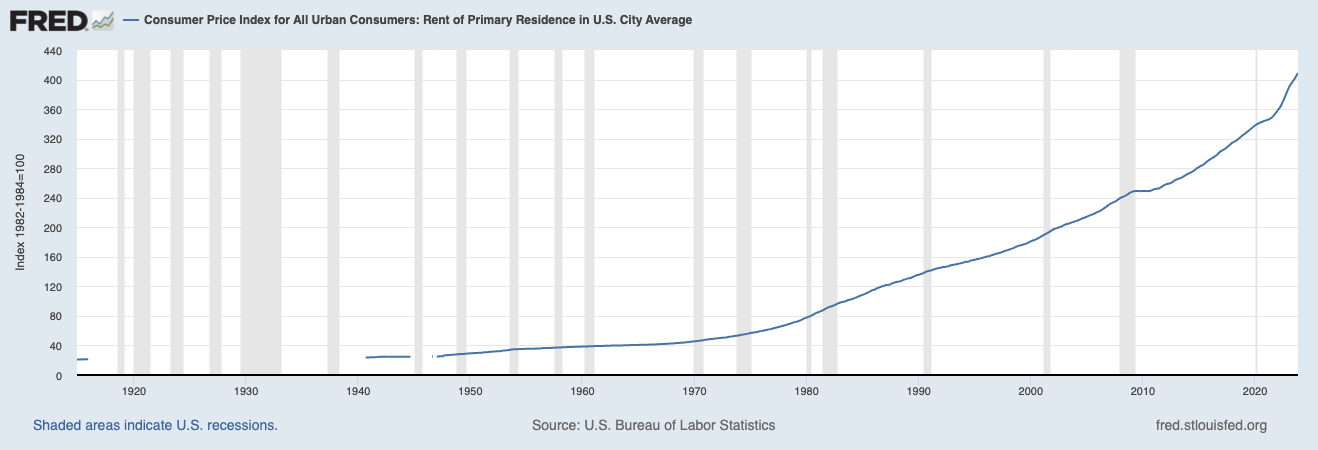

Moving on, I found other icky dealings. Landlords are not the only players in the game. Rental Property Managers have a big stake in the day-to-day operations of multiple-unit buildings, and apartment communities in general do employ a third part rental management to take care of things. This may make the job of landlords easier (especially when they own multiple properties) but it does translate into higher rents as the onus of paying for these management companies somehow makes its way onto the renter. Data shows that 8% - 12% of a month’s rent can go to the property management company. And the landlords and rental managers have one sure-fire way of ensuring high profits - by increasing the rent. Every year. Which they never fail to do, unless you are lucky enough to be in a rent-controlled unit.

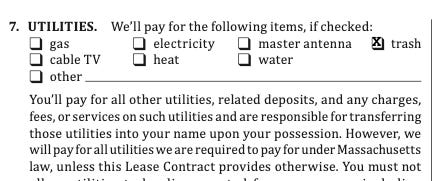

Now let’s see, If the rent is increasing every year, shouldn’t the landlords take better care of the customers, i.e, the renters? The answer is a resounding no. The burden of paying for utilities like gas, electricity, Wifi, water and even sewage falls on renters. With the way things are going, they might start asking us to deliver our trash to the landfills and recycling units ourselves. In the 21st century, the social contract that used to exist between landlords and tenants has irrevocably eroded.

II. Secondary Costs

Number one: the catch-22 situation that is Parking. If you own the home, parking is free. But if you rent, your parking costs whatever the landlord decides. I’ve paid a range of fees per apartment - from $0 to $400. In the road-loving USA, the subway and public transportation systems are too dismal to rely on which necessitates the need to have a car.

Moving Costs: Most times, one can reduce the cost of moving by using a U-Haul and having a few trusty and brawny friends around. But even then I’ve found that its hard to move without spending an average of at least 2000 USD. New furniture may need to be bought to fit the new space, old ones discarded. Some apartments don’t even provide lighting. So we may need to buy lamps, bulbs, etc to light the space. Similarly, they may not have fans. Or the humidity may be too low.

THE STUFF: The biggest silver lining of being a frequent mover is that you are forced to truly evaluate your relationship with stuff. With every move, you realize how things accumulate and how many of the random items you buy actually get used. At the time of a move, donating unused clothes and books can bring an unbelievable amount of relief. It feels good to get rid of stuff. Moving helped me keep track of what I actually use vs. what I fell for due to some excellent marketing. I’m still learning, but in my most recent move, we jettisoned fewer items and had fewer boxes to pack up. The cost of the things one can buy to fill up a new home varies from person to person and entails more psychological analysis than I’m qualified for. But the point is that there is definitely a cost associated.

III. Tertiary Costs

Moving to a new place can be exciting. The first time definitely, the second time, to see how much better it can be than the first place. The third time you have lesser expectations and move for some other practical need. After the third time, moving becomes routine, a part of your life. The real question then becomes:

How often can a person pack up their life and start over?

I am an optimistic person and I know that I have several more moves in my future so I do try to frame it as an adventure. But the reality is that, sometimes, it can be hard.

We move to a new apartment and we make friends. By the end of the year, either they move or we do. We promise to stay in touch but almost never do. For a while, we are part of a community and then, suddenly, we’re not. That is the real human cost which chronic renters everywhere are dealing with. The inability to put down roots and be a part of a solid community. Instead we have to move on, to make new friends, and to be a part of different varying communities.

It’s definitely not ideal.

With my dog, we have to socialize her with new doggy pals, all over again. As she ages, she seems less inclined to make new friends. And she perks up when we speak of her old ones. But dogs are more resilient than us humans, sooner or later, she will find her next favorite doggo.

And so the cycle continues.

For more interesting reading on the rental scene:

On the home-owners racial wealth gap - Boston Globe.

The FRED Economic Data and CPI Tracker.

The Case of Switzerland where the majority now rent.

Thanks for reading FWIT. I am going to try posting more frequently, maybe even once a week?? And if there are any topics you are interested in, please let me know!